Sewing now and in 1846

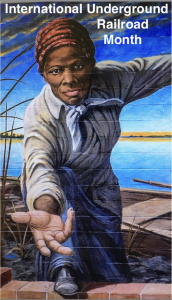

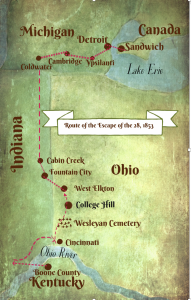

| Cincinnati’s sewing response echoes history3/24/20202 CommentsDays ago, SewMasks4Cincy was organized as a virtual sewing group to address the shortage of masks for the brave souls in the front lines of the battle against coronavirus. The people behind this effort have struck a chord, bringing together friends, neighbors, strangers–everyone and anyone who can take matters into their own hands; sewing masks, donating fabric, loaning sewing machines, picking up masks, and delivering them to beleaguered workers in need of protection against an unseen and deadly foe. Formed on March 20, 2020, by Tuesday the 24th their Facebook page had over 5,600 followers, like a car going from zero to 100mph in 3 seconds. Thanks to their dedication, thousands of masks are being made and delivered–at no cost–to those most in need of protection. One hundred and seventy years ago, desperate people among us were fighting for their lives against another invisible enemy…prejudice and its physical manifestation: slavery. Before the Civil War, the brave freedom seekers wading across the river or jumping from skiffs and steamboats at the Public Landing were those most in need of protection. Those risking their lives to cross the Ohio River arrived at a time when they were exhausted and at their most vulnerable. The penalty if they were captured was torture, physical and psychological, which would scar them for life if they survived. What they needed the most the instant they set foot on the waterfront was a way to look as if they were not in the process of escape. The clothes and rags they wore made them easy marks for professional slave catchers and outraged owners. They needed a disguise, and that’s where Sarah Otis Ernst and the antebellum, abolitionist version of SewMasks4Cincy enters the story. Descended from Pilgrims and abolitionists, Sarah arrived in Cincinnati in 1841, married a wealthy widower, and immediately established herself as a person of action, not only words. Sensing a solution to assist what she noted as “the Fugitives of whom from 600 to a thousand passed through our city annually,” she formed the Cincinnati Anti-Slavery Sewing Circle in 1846. One of the early members was Margaret Bailey, whose husband Gamaliel advanced the funds to Harriet Beecher Stowe, providing the financial breathing room for her to write Uncle Tom’s Cabin in 1851. Though the annual fairs the Society hosted were celebrated for raising funds and awareness of the need to help fugitives, and attracted such luminaries as William Lloyd Garrison and Frederick Douglass to chair the events, it was the day-to-day work of providing clean, presentable clothes to protect the breathless fugitives which did the most good. The sewing circle had direct contacts with the Underground Railroad’s quiet heroes, including Catherine “Kitty” Doram, who escaped from the slave state of Kentucky to Ohio at the age of twelve, arriving in Cincinnati with thirty-six cents to her name. She built her modest finances into one of the largest female-owned fortunes in Cincinnati and she, her brother and sister-in-law were among the first people sought by fugitives. Together with the Anti-Slavery Sewing Circle, they gathered, cut, stitched, fitted, and distributed the product of their work to protect the most vulnerable and achieve victory. We look forward to similar results from SewMasks4Cincy. We are joining their efforts in memory of women like Sarah and Catherine and encourage our members to do the same. Reprinted from the Harriet Beecher Stowe House newsletter About the author: Chris DeSimio is a financial advisor and amateur historian in Cincinnati, Ohio. He’s been interviewed on NPR and his work has been featured on WVXU for more than 31 years. He has served on the board of Tall Stacks, Inc., and is currently on the board of Cincinnati Public Radio. He was president of the Friends of Harriet Beecher Stowe House from 2012 to 2019. |

Previous Post

Previous Post Next Post

Next Post