In the early 1840s Mt. Healthy (then Mt. Pleasant) was host to a number of county-wide anti-slavery conventions. (1) Several factors made Mt. Healthy a suitable gathering point:

- It was located along an important thoroughfare, the Hamilton Road (as it was then called), which in the 1830s was improved and became the Cincinnati and Hamilton Turnpike.

- There was an established village here, as a natural congregating place. There were two taverns, inns for people to spend the night, by 1815, and a meetinghouse available for conventions.

- There was a Presbyterian Church in Mt. Pleasant since 1829; this denomination attracted a high proportion of abolitionists, and since it was the only Presbyterian church between Cincinnati and Hamilton, Ohio it would have been a natural gathering place for anti-slavery meetings.

- There was a Free Meeting House available for use, constructed in 1825. It was already a familiar gathering place for the various denominations that had yet to construct their own church buildings.

- Hostility toward abolitionists in the city of Cincinnati was extreme. In 1836, pro-slavery mobs had twice attacked the offices of The Philanthropist and its editor, James Birney, had only by luck escaped death at the hands of the mob. Holding the conventions outside the urban center would have carried less risk of attack.

At the time Mt. Pleasant (the name was generally appended by “Hamilton County” to distinguish it from the Quaker abolitionist town of the same name in Jefferson County, in southeastern Ohio) was a thriving village. It was the center of commerce for residents from present-day College Hill to the north edge of Hamilton County. The town of Hamilton in Butler County was twelve miles to the north, and the city of Cincinnati was twelve miles to the south, so Mt. Pleasant was a midway point, a rest stop for travelers and a place for business for residents of the area. Travelers on the Hamilton Turnpike could stop to fortify themselves with food and drink at one of the taverns in Mt. Pleasant. They could purchase supplies at the store, and have their wagon repaired or their horse re-shod. (2) The presence of the taverns made it a convenient overnight stay, as some of the conventions lasted two days.

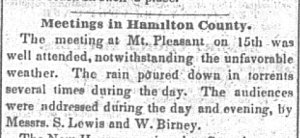

Records show that conventions of all political hue took place in Mt. Pleasant. There were Whig conventions in the mid 1830s, and Democratic and Republican Party conventions alike recorded in the several Cincinnati newspapers. We focus here on the anti-slavery conventions. (3)

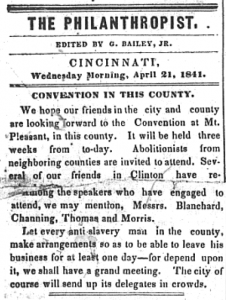

Documentation of local abolitionist activity, in the form of personal records is scarce, but the anti slavery newspaper The Philanthropist, published in Cincinnati, is a rich source of firsthand reporting on the conventions.

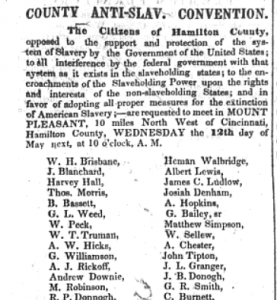

The convention of May 12, 1841 was hosted by the Mt. Pleasant Presbyterian Church. It was a “free discussion on the principles of anti-slavery.” The abolitionist minister Jonathan Blanchard, of the Sixth Presbyterian Church in downtown Cincinnati, was the keynote speaker. Blanchard had studied at Lane Seminary in 1837-38 and as a white minister preached in colored churches.

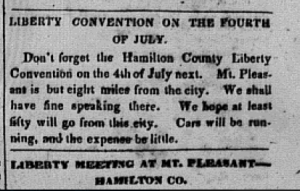

On July 4, 1842, the “Liberty convention for Hamilton County” established organizing principles and selected a slate of candidates for state office.

On August 1, 1844, “a large and spirited meeting” of the Liberty men of Hamilton County was held at the Free Meeting House, for the purpose of nominating candidates for office under the Liberty Party. (4)

At the national level, a slate of candidates was named for the 1840 Presidential race. James G. Birney, a converted former slaveowner, was chosen as the Presidential candidate during the 1840 and 1844 races. Local Liberty groups chose Liberty Party slates for state, county and local offices, and conventions were held to promote their campaigns.

The conventions were well attended: the paper’s announcement for the May 1841 convention includes a list of the names of 320 locals who’d signed on in support. The image below is a small portion of that list, which can be found in its entirety in the Philanthropist, 5 May 1841.

The anti-slavery society was progressive in its inclusion of women, and the 9 August 1844 Philanthropist reports of a recent convention that

“One thing affords us a great deal of pleasure – it was the large number of ladies in attendance. Women’s countenance and encouragement are peculiarly needed, and peculiarly appropriate, in the cause of Human Liberty.”

Notes:

1. For notices of and reports on Hamilton County anti-slavery conventions, see Philanthropist various. E.g. May 1841, 12 Apr 1841, 20 June 1842, 9 July 1842, 6 Sept 1843, March 1844, 26 Jun 1844, 9 Aug 1844, et al.

2. Information on economy of Mt. Healthy extracted from 1850 census records.

3. The Cincinnati Enquirer, recorded Democratic conventions and pejoratively referred to the “black Republican” conventions held here; the Cincinnati Daily Gazette also reported on conventions.

4. In 1840 members of the American Anti-Slavery Society, frustrated that the two leading political parties were making no progress toward ending the institution of slavery, voted to establish a third political party, the Liberty Party. The two major political parties – the Whigs and the Democrats – were fielding candidates for the Presidency who would not oppose slavery. The Congress was deadlocked as northern Whigs soft-pedaled on the issue so as not to spark conflict with the southern Democrats. Both parties recognized the economic benefits of slavery; the power of the southern slaveholders seemed to have both parties in its grip. Citizens petitioned Congress to end slavery, yet the legislature barred the reading or discussion of these petitions: known as the “gag rule.” Anti-slavery advocates saw this abridgement of their Constitutional right of free speech adding insult to the injury of slavery, which they felt was not only morally wrong but against the very principle of liberty upon which the American republic was founded. Still, among abolitionists the foray into electoral politics was controversial, and it was amid much disagreement that the Liberty Party was established. For a detailed treatment of the Liberty Party nationally and in Ohio, see Reinhard O. Johnson, The Liberty Party, 1840-1848 , (Louisiana State University Press, 2009).

Written by Karen Arnett, February 2014

This is so helpful in understanding why these conventions were held in Mt. Pleasant at this time. Since the College Hill Presbyterian church was not founded until 1850, All the Presbyterians from College Hill and Mt. Healthy worshipped and worked together throughout this time. SO good to have the newspaper articles in the article so you can get a feel for the times!