The following pages are an excerpt from a typed manuscript of a talk given by Frank Woodbridge Cheney in 1901 to a literary group in Hartford Connecticut. He describes the involvement of his father in the Underground Railroad. This important source document is held by the Connecticut Historical Society, OCLC #32695623. (For the complete manuscript, see link below, before footnotes.)

Frank Woodbridge Cheney (1832-1909) was the eldest child of Charles Cheney (see page on Cheney on this website for more information). The author lived with his family here in Mt. Healthy (then Mt. Pleasant) from 1835-1848. For more information about Charles Cheney (1803-1874), see the page under “People” on this site.

The Cheney Family was well established in upper society Connecticut circles. Their Cheney Brothers Silk Manufacturing Company in Manchester, in production from 1838-1955, was the primary economy of Manchester., and the area was declared a National Historic Landmark District in 1978.

(This is copied verbatim from the manuscript. “No. X” is the Monday Evening Club’s numbering. A disclaimer: the language of the following manuscript expresses views and opinions on race in a manner that the editors of this website do not condone. Please remember that the manuscript contains important historic content and must be read as a historic, and not a contemporary, document. )No. X

Subject: The Underground Railroad.

The Hartford Monday Evening Club

at the house of Rev. Henry Ferguson, 123 Vernon St., February 11, 1901.[1]

[Pg. 1]

My introduction of the subject of the Underground Railroad will begin with an account of how I came to know about it.

My father took his family to the West in 1835, when I was between three and four years old. He settled on a farm at Mount Healthy, about ten miles north of Cincinnati, which was at that time one of the most important cities of the west. The country about us was very thinly settled, and clearings had to be made when new farms were brought under cultivation. Fortunately this hardest of all work for the early settlers had been done by our predecessors, and we escaped the hardships incurred in making a clearing of the forest and breaking the virgin soil. There was no lack of hard work in farming, however, under the most favorable conditions. In the thirteen years we lived at Mount Healthy, I grew up to the age of sixteen. There were no servants at that time. [2]The hired men and girls barely allowed themselves to be called help and had to be treated on terms of social equality, which at times came to be very irksome. This may have been one of the governing reasons why my father and mother, after many trials with this kind of white help, came finally to rely upon a family of colored people who came to us in some way I do not now remember.

[Pg. 2]

They seem to me now to have belonged to us and we to them, in much the same way that good old Southern families and slaves lived together, with common interests and affections. [3] They certainly had brought from slavery the fixed belief that what ever belonged to master belonged to them too, and they did not fail to share it when they could: houses, lands, animals and especially food of all kinds they looked upon as community goods, which they kindly allowed us to share with them. I particularly refer to these southern traits, for they have had an important bearing upon my feelings about the blacks ever since.

The most marked member of our household was known only as “Grand-dad.” I believe his family name was Dunlop, but this was never used. He had been a slave in Georgetown, near Washington, and was full of reminiscences of the aristocracy, “the quality,” he called them, of the old towns. He held himself far above the common negroes around us, most of them runaways from the South. [4]He was of the Uncle Remus[5] type, and we had all the Uncle Remus stories from him at firsthand. Never since have any romances been so exciting as those Grand-dad told us. He was full of valuable knowledge, and

[Pg.3]

taught us where to find all the game, birds and beasts and fishes of the region about us. I could make now out of an old hollow log a rabbit-trap after Grand-dads pattern, which, baited with a sweet apple, with unfailingly catch a rabbit every dark rainy night, if there were one within a mile. His figure-four quail-traps were unfailing. His daughter, Maria, was our cook, and the real head of the family.[6] There were four sons, ranging from ten to eighteen. Jim was the eldest and became my father’s confidential man, in emergencies to come later on. Then came George Washington, Maximilian Adolphus, (Mack for short,) and Wes, named after the distinguished Methodist preacher, Wesley.[7] Grand-dad was an earnest Methodist, and a good old pious black man of the best kind. I would have trusted him with untold gold, if I had ever had it. He did not go into his closet to pray, but every night he knelt down by his bedside and prayed so you could hear him all over the place. This was probably because he felt that he was attending to religion for the whole family and knew how much it was needed. I wish he could come back and pray for my children and grandchildren. You cannot get prayers of that

[Pg. 4]

kind now, full of inspiration and love: they were addressed directly to the Lord, and not to a properly cultivated congregation.

My playmates and companions were Jim and George, Mack and West, and I grew up with them till I was sixteen years old, and knew all they did and a good deal more about many things; for I could read when I was seven years old, and went to a young ladies’ boarding school as a day-scholar[8] and afterwards to Carey’s Academy at College Hill, near by.[9] They were a good healthy set of young animals, true and honest, except when temptation came their way in the shape of something to eat. But whatever faults they had I afterwards found repeated in boys of the best families whom I knew at school and college in Providence, Rhode Island. After a while it seems to dawn upon me that we were having occasional transient guests of sable hue,[10] who arrived after dark and went away before light. My curiosity regarding them became so engrossing that my father thought it best to trust me with the secret, which was a dangerous one to get out, that we were harboring and forwarding runaway slaves, and that our house was the first station out of Cincinnati on the Underground Road.[11] There were

[Pg. 5]

no railroads then, but afterwards the name became “Underground Railroad” in other parts of the country and soon became general. Nothing ever came to me which brought such a feeling of individual responsibility as did the knowledge of this secret, which my father thought it was best and safest to impart to me, though I was only a boy ten or twelve years old. It was a thrilling sensation when a mysterious knock on the window came in the middle of the night, something like a telegraph call, one, two, three, – the signal agreed on with confederates that the slave was at our door, or that important news was to be told. I slept in the same room with my father and, being a boy, did not always hear these signals, but I did awake sometimes with a great start, for I knew what it meant. The door was opened cautiously, and after a whispered conference to make sure that all was right, the conductor and his charge were admitted and full explanations given about the case, and action taken according to the emergency. If it was thought that there was likely to be a hot pursuit after the runaway slave, he was fed and sent on as quickly as possible. Jim was called, as he knew he might be at any minute, to hitch up one of the best horses to a light running wagon with black

[Pg. 6]

curtains, which could be fastened down on all sides, so that nothing could be seen of the occupants, except on the front seat where the driver sat. Jim was the conductor of this underground train, and his duty was to drive the wagon to Hamilton, which was a large town about twelve miles north of our place, where his passenger was turned over to another friend, who in turn sent him to a settlement of Quakers in Lorain Township[12] ; the same one which is vividly described by Mrs. Harriet Beecher Stowe and Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Thence there were several routes by which Canada could be reached, the end of the long flight for freedom. By the time I was a dozen years old, I was familiar with all the details of the Underground business on the routes from Cincinnati to Mount Healthy, our place, and from there on to Hamilton and the Quaker folks. Occasionally I was allowed to go with Jim on these trips to Hamilton, which I was mighty glad to do, for there was an exciting sense of adventure about those nocturnal journeys, always possible to involve us in the capture of our whole outfit and no telling what other risks, in the way of personal violence, fines and imprisonment, for harboring and aiding runaway slaves to escape. I remember vividly one fine-

[Pg. 7]

looking, powerful man showing us a pistol and telling us he would be killed before he would be captured, and it was not vaporing talk either on his part. Sometimes we had to keep our guests out of sight for several days, if it was suspected that they were being followed and that a lookout was being kept on our house. Once we had a man and wife and three children kept out of sight for three or four days, as it was known that we were under suspicion and the slave-hunters were on their track. Father was the president of the turnpike from Cincinnati to Hamilton[13], about twenty-two miles long, which he was instrumental in having built, and which in its day was looked upon as a great undertaking, bigger than a railroad clear across the state of Ohio would be now. This gave him control of all the toll-gates, and the appointment of the toll-gate keepers. It was remarkable how uncommunicative these gate-keepers were about having seen anybody on the road that night, and so with the suggestions they had to make that the parties that were being looked for must have taken one of those by-paths down by the foot of the hill so as to avoid paying toll – “Lots of people just mean enough to do that. They would go five miles further and ford the creek,

[Pg. 8]

to beat the pike out of a quarter.” When the hunt was very warm and it was asked if a close wagon with two niggers had not gone along last night, it was allowed that last night, or perhaps the night before, a team did come along, but it belonged to a man he knew to be alright, who was sending some truck up to Hamilton, and the white boy was his son going along to look after it. Unfortunately for the interest of my story, we were never caught and never had any serious adventures, but were always on the lookout for them. Our lucky escape, however, was not due to good luck alone, but to the constant watchfulness of all who were engaged in the work of the Underground road along our route. There were frequent reminders of the great dangers incurred, for often the runaways were overtaken or waylaid, by the slave-catchers, severely handled if they resisted or attempted to escape; and their friends who were caught aiding them, (slave-stealers they were called), suffered severely in person and property. Mr. Van Zandt, a friend of my father, who I believe was connected with Lane Seminary, was thrown into prison and heavily fined and practically ruined by the legal expenses attending the trial of his case, which was

[Pg. 9]

finally carried up to the Supreme Court of United States, where he was ably defended by Salmon P. Chase, who came to be known as the Attorney General of the Underground Railroad.[14] He afterwards was President Lincoln’s Secretary of the Treasury, and to him mainly we owe our system of National Banking. Mr. Chase was often at our house with his invalid wife and little daughter, who was afterwards Mrs. Kate Chase Sprague.[15] Mr. Chase was in every way a very superior man, and thoroughly in earnest in carrying forward all well directed efforts to bring about the emancipation of the negroes. His eloquence in their behalf brought him prominently before the people of Ohio and of the whole country, and laid the foundation of his successful career as a politician, statesman, financier and chief justice of the Supreme Court of United States. His ambition, and a worthy one, was to be the President of the United States. He died of a broken heart because he did not attain his end. So did Daniel Webster and Horace Greeley.

President Rutherford B. Hayes, when a young lawyer, took charge of a good many cases for fugitive slaves in Cincinnati. It was a labor of love, for he charged nothing for his services and probably could not have got anything if he had. His reward was great in after days, and his work was not forgotten.

[Pg. 10]

This incident is told by Professor Siebert.[16] A slave woman escaped from Kentucky in 1856, and found shelter with her four children in the house of a colored man near Cincinnati. She was captured; rather than see her children returned to slavery and doomed to the fate she had hoped to save them from, she made up her mind to put them to death. When her master was preparing to carry them across the river she began to carry out this intention by killing her favorite child. Before she could go further with her awful task, she was arrested and put into prison. The efforts made to prevent her return to bondage were unavailing, and she was delivered to her master with her three surviving children. Mr. R.B. Hayes, who lived in a pro-slavery street in Cincinnati at the time, told one of his friends that this tragedy converted the whole street, and that the day after the incident a leader among his pro-slavery neighbors called at his house and declared with great fervor: “Mr. Hayes, hereafter I am with you. From this time forward I will not only be a black Republican[17], but I will be a damned abolitionist.”[18] You cannot realize at this day the bitterness and opprobrium of this name. The recollection of hearing my father being called “a damned Abolitionist” by the young

[Pg. 11]

savages I went to school with in the village rankles in my heart yet, though I am proud of the name now. Then it was intended to express all that was held most odious and infamous and beneath contempt.

[1] The Hartford Monday Evening Club was founded in 1860 by the theologian Rev. Dr. Horace Bushnell. It was a small group, by invitation only, for the purpose of intellectual inquiry and discussion on topics chosen by its members. Mark Twain was a member from 1871 to 1891.

[2] A telling comment about social equality in the early days of Mt. Healthy and Springfield Township. The majority of immigrants to the area up through the 1830s were farmers and tradesmen from the east: New Jersey, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania. Their access to land and independence fostered a climate favorable to abolition (favoring human rights); later censuses show a newer wave of immigrants from Ireland who may have seen emancipation of enslaved people as posing competition for scarce jobs.

[3] The author’s comments about African Americans reveals an attitude commonly held in mainstream society, and even by most White abolitionists, of not favoring social equality for Blacks and Whites. A very interesting book about this lack of social equality even among the egalitarian Quakers is Fit For Freedom, Not For Friendship: Quakers, African-Americans, and the Myth of Racial Justice, McDaniel and Julye, 2012, Quaker Press

[4] This comment agrees with Census data that indicate a growing African American population in Mt. Healthy through the years 1840-1860. Before the Civil War the neighborhood seems to have been a relatively safe haven for African Americans

[5]Uncle Remus was a fictional title character in the Uncle Remus books published in 1881, the narrator of animal stories, such as Brer Rabbit, for the enjoyment of White children. “Uncle Remus” grew to be a cultural stereotype: the elderly self-effacing and contented Black man who spoke in a strong dialect and did not threaten White people’s view of their own cultural superiority.

[6] Mrs. Cheney (Waitstill Dexter Shaw) died in 1841. Two daughters died on 1836 and 1841.Thereafter Charles Cheney and his son Frank Woodbridge and Knight Dexter were left alone in the household. Hence the comment that Maria was “the real head of the family.”

[7] Census records corroborate these assertions. Although the patriarch of the Dunlap family was not found in census records, the 1840 census recorded a Free Black male in the age category 55-100 in the Cheney household. (That census recorded no names other than that of the head of household and a simple count of all the other members of household according to race and age category.)

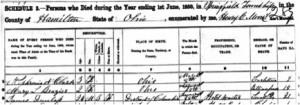

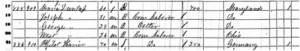

Springfield Twp, line 425, p. 62 of 1850 census: (Click on image to enlarge.)

Ln 425, Household 425: Maria Dunlap, age 40 F[emale], B[lack], value of real property $600, born District of Columbia; Joseph A. Dunlap, age 16 M, B, born Ohio

Death Record from Springfield Twp, 1850, for James Dunlap : (Click on image to enlarge.)

James Dunlap, age 24, Male, Black, Free, born District of Columbia, date of death Jan. 28, occupation Hotel Waiter, cause of death Smallpox, number of days ill 21

Springfield Twp, line 885, p. 23 1860 census: (Click on image to enlarge.)

Ln. 885 Household 909 Maria Dunlap age 40, F[emale], B[lack], value of real property $700,born Maryland, cannot read or write; Joseph Dunlap age 31, M, B, [occupation]Comm. Laborer, born Maryland; George, age 29, M, B, Ostler; West, age 29, M, B, born Ohio, Comm. Laborer

[8] Hygeia Female Athenaeum, founded in 1840 by David Burnet. Its location was roughly across Hamilton Avenue from the current location of Cary Cottage.

[9] Cary’s Academy for Boys was founded by Freeman Grant Cary in his home, now at 5651 Hamilton Ave. (National Register of Historic Places), in 1832. It was a success and the school continued to grow, with new buildings clustering about Hamilton and Belmont Aves. It finally was so large that in 1845, a board of trustees was chosen and the brick Farmers’ College was built. The author’s father Charles Cheney was on the first board of trustees of the college.

[10] Sable is an old fashioned adjective denoting dark brown or black. It comes from the color of the fur bearing animal by the same name. It was used by Whites to describe the skin color of Africans and African-Americans in the 19th century and into the 20th.

[11]There were several possible routes from Cincinnati northward: via Vine Street, along the Mill Creek and either via Compton Road near Carthage to Mt. Healthy or north through Glendale, along the “Hamilton Road” (currently Hamilton Avenue,) up present-day Gilbert through Walnut Hills. We do not know exactly the route that Cheney here refers to.

[12] Lorain County, not township, is the site of Oberlin College, which was also heavily involved in the Underground Railroad.

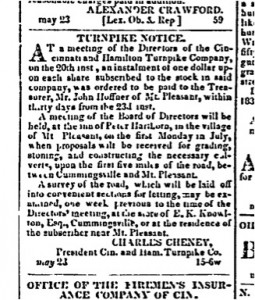

[13]Ad from the Cincinnati Daily Gazette, 23 May 1837: (Click on image to enlarge)

[14] John Van Zandt was a farmer that was caught in 1842 transporting a wagonload of escaping slaves from Lane Seminary in Walnut Hills to his home near Glendale. He was defended by Salmon P. Chase before the Supreme Court. Van Zandt, who lost the case, died a pauper due to court fees and fines in 1847 before the trial was over. So did the slave owner that sued him. Van Zandt was immortalized as the character John Von Trompe in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

[15] Charles Cheney and Salmon P. Chase may have been planning their political campaigns or organizing local anti-slavery conventions: both ran for office on the anti-slavery Liberty Party slate in various mid-1840s elections. (See article on this website about the conventions at the Mt. Healthy Free Meeting House. )In 1840 members of the American Anti-Slavery Society, frustrated that the two leading political parties were making no progress toward ending the institution of slavery, voted to establish a third political party, the Liberty Party. The two major political parties – the Whigs and the Democrats – were fielding candidates for the Presidency who would not oppose slavery. The Congress was deadlocked as northern Whigs soft-pedaled on the issue so as not to spark conflict with the southern Democrats. Both parties recognized the economic benefits of slavery; the power of the southern slaveholders seemed to have both parties in its grip.

[16] Professor Wilbur H. Siebert (1866-1961), a historian who taught at Ohio State University, and over a period of 50 years documented the Underground Railroad through the recollections of direct participants as well as descendants. A short video overview of the Siebert Collection, by the Ohio Historical Society, can be seen here. Cheney would have been familiar with this work through Siebert’s magnum opus The Underground Railroad From Slavery To Freedom which was first published in 1898.

[17] The term Black Republican was used by Democratic newspapers such as the Cincinnati Enquirer as a derogatory reference to adherents to the newly formed Republican Party, which was the anti-slavery party.

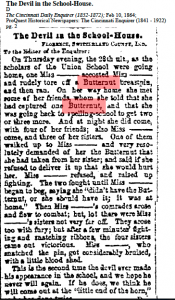

[18] In border areas such as southern Ohio, the population was polarized over the issue of abolition. The following article in the Cincinnati Enquirer, 1864, (reprinted from Indiana) shows how fights broke out even among schoolchildren over the issue. While this article is from the time of the Civil War, it is easy to imagine the same kinds of fighting happening in earlier years over the “damn abolitionists” in the community. (The butternut was an emblem worn by northerners who favored the continuation of the institution of slavery.)

(Click on image to enlarge.)

Karen Arnett, 2 February 2014, karenarnett@gmail.com