John Hatfield and his land in Carthagena, Mercer County, Ohio

[Betty Ann Smiddy has put together a background history of the black settlement Carthagena, in Mercer County Ohio. This serves as helpful context and supplement to Smiddy’s recent booklet Hatfield: Barber, Deacon, Abolitionist.

Mercer County was young when Dorcas Moore and her eight children presented emancipation papers[1] from Harrison County Kentucky, recorded Dec. 30, 1830 by the Mercer Co. Clerk of Court at St. Mary’s in accordance with the state of Ohio’s Black Laws. The Moores settled in Marion Township, about three miles north of the line drawn by the 1795 Treaty of Greenville that separated Native American lands from those of the settlers. Mrs. Moore’s third son, Charles, had purchased his freedom and then bought his family’s freedom for $2,200.[2] He bought land for more than a decade where they settled, which attracted other pioneers. In December of 1840 he platted a village in the middle of this community, naming it Carthagena. By the time of his death, Charles[3] had accumulated hundreds of acres.

The fertile land there was sparsely settled and was located at the far southern edge of the Great Black Swamp, which stretched from the shores of Lake Erie to Ft. Wayne, Indiana. This swamp was in places impassable wetland, encircled by a wooded moraine left over from the last glaciation. It also had endemic malaria.

Early pioneers there had a huge job before them. Before crops could be planted, the land needed to be cleared and/or drained. A cabin had to be built and fences put in to contain the livestock from the fields. Underbrush was destroyed in a controlled burn to facilitate moving about in the forest to reach the trees. Trees were girdled about 3 feet up the trunk from the forest floor by removing a yard wide swath of bark around the tree. If girdled in summer, the tree would die over winter and be ready to be felled the next spring. According to Anna-Lisa Cox’s book The Bone and Sinew of the Land,[4] once the land was cleared, “plowing one acre with a single-blade plow required nine miles of walking on rough mud.”[5] She continued that tree roots large enough to stop the team were encountered every eight feet[6] and would need to be hacked away. To clear forty acres of land that had once been forest, it would take twenty years for the rocks and roots to be gone[7] so that horses could be used for plowing rather than oxen. Corn was sometimes left standing in the fields to dry rather than brought in for winter storage. If gathered in, it had to be kept dry during winter. If grain was planted, to scythe a field was slow, only about one quarter of an acre a day.[8] Then the grain would have to be beaten from the stalks and winnowed and the stalks gathered up from the fields. Everything was labor intensive.

The Moore family settled in Marion Township among a small number of white settlers, who were mostly from Connecticut.[9] The township was sparsely settled until Ohio joined the canal boom that had brought prosperity through commerce in other states. Ohio was one of the fastest growing states west of the Alleghenies and money was easily raised by land speculation, promising a high return for a moderate investment.

In 1825 Ohio proposed a canal from Cincinnati to Dayton following the Miami River, with the hope that if it proved successful, that the canal would be extended north to Lake Erie. An act by Congress on May 24, 1828 aided in this extension by granting “a quantity of land, equal to half of five sections in width,[10] on each side of said canal, between Dayton and the Maumee river, at the mouth of the Auglaize, so far as the same shall be located through the public land, and reserving each alternate section of the land unsold to the United States…and which land, so reserved, shall not be sold for less than two dollars and fifty cents per acre…”[11] This created the “canal lands”[12] in Ohio, passing in part through Mercer County. The sale of these lands to private individuals paid for canal construction. Congress also included a “clawback clause” that if the Miami Canal extension was not started in five years and completed within twenty years, Ohio would have to pay back to the United States the entire cost of the lands; any land purchaser would still have a valid title and owed nothing; all of the unsold land reverted back to Congress.

To make the canals flow at sufficient speed and depth to carry boats year around, water had to be artificially provided either through a reservoir that retained and released it or by river. The swamp lands in Mercer and adjoining Auglaize counties were drained and a huge reservoir, now known as the Grand Lake, constructed at St. Mary’s in 1843. While some lands were thus drained for farming, other farmlands were sent underwater and the farmers were not compensated. Angry farmers so affected in Jefferson Township, where the bulk of the lake resides, later in that same year breached the reservoir. They were joined in this action by several prominent local officials. While there were a few arrests, there was no prosecution. This created a precedent that a popular sentiment could override a law without consequences if elected authorities agreed with the ideas of the “mob” against an outside authority, such as the state. This behavior was soon to be repeated.

There was another unusual clause that Congress attached to the early deeds in the canal lands. One of the first purchasers in Marion Township’s canal lands was John Hatfield. On Nov. 14, 1835 Hatfield bought 94.64 acres for $118.30.[13] In his deed the following is included: “…Act to aid the State of Ohio in extending the Miami Canal from Dayton to Lake Erie and to grant a quantity of Land to said State to aid in the construction of the canal Authorized by law and for making donations of Land to certain persons in Arkansas Territory[14] which said tract of land has been fully paid for equally to the sections of the Register…”

Arkansas Territory? Why should Ohio donate land to people in Arkansas? The answer lay in what else happened in 1828. The Treaty of Washington[15] was signed May 6, 1828 whereby the Arkansas Cherokee ceded their land in Arkansas and moved west into what was designated as Indian Territory. (It later became the state of Oklahoma.) Those white settlers who were in those western lands had to move east, into Arkansas Territory. The Treaty promised permanently seven million acres of land for the Cherokee Nation, “a perpetual outlet west” as far as the “sovereignty of the United States extends,” and to make limited payments to the Cherokee Nation. The settlers were promised two quarter sections of land in the Arkansas Territory for relocating east. The treaty was ratified the day before the canal act (which established the canal lands) was passed. Tacked onto the end of the canal act is the clause concerning the donation of land in Arkansas Territory for the settler/Native American land swap, which, although not stated, Ohio appears to have aided in funding.

Why did Hatfield invest in land at that location? Probably because of his association with Augustus Wattles.

Wattles, born in 1807 in Lebanon, Connecticut, attended New York’s Oneida Institute which prepared young men for “the millennial struggles of transforming American society.” A manual labor college, it was interracial, radically liberal and was once characterized as “abolitionist to the core.” A group of students[16] led by Theodore D. Weld left Oneida in 1833, rafting down the French and Allegheny Rivers, travelling to Lane Theological Seminary in Walnut Hills whose president was Lyman Beecher.

Originally for Colonization, by the time the “Lane Rebels” chose to leave Lane Seminary because of its stilted racial views, Wattles changed his beliefs as a result of the debates held by the students in Feb. 1834. For 18 days they held debates over the question of Colonization vs. emancipation. He realized that many of the free blacks hated the idea of relocating to Liberia. He came to share their views, believing they should have both freedom and equality within the United States. Wattles believed they needed education in skills that would enable them to succeed. Augustus did not transfer to Oberlin College after leaving Lane Seminary but chose to be a teacher in a school for African Americans in nearby Cumminsville.[17]

In 1835 Weld, Wattles and others toured the east coast, raising awareness for the abolitionist cause and touting the need for education. At a lecture in Oneida, New York, Augustus said he could accommodate black women and girls rather than only men and boys, if he had female teachers. Susan Elvira Lowe, age 17, agreed to come to Cincinnati to teach in the Cumminsville school. Eventually, three additional women volunteered to teach after hearing his lectures. Their travel expenses from New York to Cincinnati and their salaries were paid by Arthur Tappan of New York.[18]

When these “Cincinnati sisters” arrived they found it difficult to get housing in white boarding houses and were given hospitality by the black community.[19] As a consequence, they were reviled, hissed, threatened and cursed by their own race when they walked in public. They were not disheartened and continued their vocation. Wattles and Susan drew close and married in 1836.

John O. Wattles, Augustus’ brother, also taught in an African American school for boys in Cincinnati. By then, Augustus was the head teacher of the black schools in Cincinnati, some of which were situated in the basements of black churches. Augustus worked with the Underground Railroad while he was in Cincinnati and it is here and through the black churches that it can be speculated Wattles and Hatfield, a deacon at Zion Baptist Church, became acquainted. Having lived the oppression of Cincinnati’s “Bucktown” and “Little Africa,” Hatfield could understand Wattle’s ideas.

The Wattles brothers’ work impressed Theodore Weld, who recommended to the American Anti-Slavery Society that Augustus be appointed as a national free agent. In 1836 the AAS did include him as one of “the Seventy” whose lectures laid the abolition groundwork at a local level. He traveled throughout Ohio and Indiana, speaking of the necessity of abolition, education and the virtues of relocating freed blacks into rural areas where they could form their own communities and farm. He also solicited cash donations to be able to buy land for such a community that he envisioned. Augustus traveled to Canada, Ohio and Indiana seeking a site and picked Mercer County because of its low population, land cost, and fertile soil. The Moores were also there and their presence had drawn other black farming families.

Due to the riots in Cincinnati, Wattles believed that education was not enough for blacks to succeed in an urban environment. Poor housing, low wages, crime, crowded conditions and unrelenting prejudice coupled with the ever present threats of violence led him, and others, to advocate that free blacks needed to begin again in a rural place that they could thrive. He joined a movement in Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin and Michigan that saw 338 free African American farming settlements founded.[20] Of course, these communities also aided freedom seekers and were part of the Underground Railroad.

Wattles wrote in 1838 “…When land can be bought for $1.25 per acre, it is folly for men to hang about cities, and, procure a scanty, doubtful existence. A man in the city can have only what he earns with his hands. In the country, if he calculates, he can set the elements and all nature to work for him…Every poor man in the east, who can raise fifty dollars, ought to lay it out in land. This will buy him forty acres; or one hundred dollars will pay for eighty acres…In Ohio, in Indiana, in Illinois, or in the Wisconsin territory, in Michigan, in Canada, are thousands of acres lying waste and uncultivated, as fertile land as any in America, and naturally a much stronger soil than any you will find at the east…My conclusion now is, for you to inform all the eastern friends, and represent the case to them. Collect their money, and send an agent, one of their own number, out here by next August. If they conclude to do this, and you think any number of them will enter into the plan, I will go through the land that is for sale, and make the best selections that I can find…” [21]

Augustus started buying land in Mercer County in 1835 near the farming community in Marion township that had developed around the property of Charles Moore and his family. Wattles bought 195 acres initially with monies already collected from the new settlers and donations. He set out from Cincinnati with about fifteen families and oxcarts loaded with necessary supplies.

Wattles wrote: “In about three years they [the African Americans] owned not far from 30,000 acres. “[22] This included land that Wattles also bought in Granville and Butler townships.

There is no evidence that Hatfield ever lived on the property he purchased. He paid his land taxes regularly. I believe he rented land to a tenant farmer and was either paid in cash or in a share of what was raised on the land.

To further attract migrants Augustus and Susan settled there on an additional 190 acres they purchased for a manual labor[23] school. Word of this undertaking was presented at anti-slavery societies seeking donations.[24]

Wattles reported in The Philanthropist[25]in 1837 that within sixty miles of where he lived, there were five African American farming communities. Where his manual labor school was located, the “people own all the land on the road for ten miles. Between 75 and 100 individuals have purchased here. Two years ago this fall, the first land was entered by them. – This year, one man has thirteen acres in corn and five in wheat….One is putting up a steam saw.” The school was about three miles from the canal.

Named the St. Mary’s Manual Labor School, it was racially integrated and co-ed. In addition to “ordinary studies” he planned to add agricultural and horticultural classes, physiology, mathematics, Latin, Greek and Hebrew. His brother John also taught there. A shop was going to be added “in which boys will be taught to stock ploughs, make harrows, bar-posts and window sash. My father-in-law, who is a carpenter, will oversee this. – He came to the settlement from Oneida on purpose. My wife also thinks of trying her hand with the females. As a preparatory step, she has this year planted a nursery of mulberry trees, which she thinks will furnish employment for 15 or 20, or more girls…”[26] It was anticipated that a hundred students could attend.

Wattles began to experience ill health which ended his lecture tours in 1838. He concentrated on his school, his farming and his growing family of four children. Moore platted Carthagena in 1840 across the road from the school. Hatfield’s property was just north of the school. Moore had previously set aside land for an African Methodist Episcopal church. In 1841 Hatfield set aside one acre on the corner of his property for the “Colored Baptist Church of Beaver Creek.” The log church was for the “Free Will Baptist” denomination.[27] It eventually burned and a new church was erected, which stood until 1934.

The school achieved a modest success. It received a major financial boost in November, 1842 with a $20,000 donation from the trustees of the estate of Samuel Emlen, a New Jersey Quaker. He left a bequest in his will to support the education, including agricultural and mechanical, of boys “of African and Indian [native American] descent, whose parents would give them up to the institute.” [28] Wattles traveled to Philadelphia and made a case for his school and the success of the black community surrounding it, bolstered by letters of recommendation from James Birney and other abolitionists of his acquaintance. The school and farm was actually purchased from Wattles, he being hired as superintendent, and was renamed the Emlen Institute. A library of nearly 1,000 volumes was donated by publisher Charles Whipple of Newburyport, Massachusetts.

In describing their community in 1843, the residents wrote a lengthy description of their lives and industry.[29] In addition to a saw mill and grist mill, there were meeting houses, a school, cleared 1,00 acres, “… made and laid up, 50,000 rails, and built at least two hundred different kinds of buildings, (to say nothing of some $10,000 which individuals of us have paid for our freedom,) besides having in our settlement a hatter, a wagon-maker, a blacksmith, a tanner, a shoemaker, carpenters, masons, weavers,…We have also built several brick kilns …We receive no more damage from our white neighbors than we do from one another.” The newspaper article says, “They [the whites] attend our meetings, come to our mill, employ our mechanics and day laborers, buy our provisions, and we do the same by them. That is, we all seek our convenience and interests without regard to color.” It also was a temperance community. Two years later another newspaper article gives the yields in bushels from one 130 acre farm: 400 wheat, 1,000 corn, 300 rye, 400 oats and 30 tons of hay.[30]

This hard-won utopia was not to last. The incoming waves of immigrants were German Catholics who embraced Jacksonian[31] Democratic politics. While they were hard working, they believed that land speculation had strangled the development of industry and agriculture in Mercer County.[32] They were also against free blacks and feared racial equality. [33]

Wattles received letters threatening violence against the school and surrounding community. Angry white citizens accused the school of attracting and shielding freedom seekers. Demanding that he close the school and move, residents of Carthagena were harassed and began to feel uncomfortable.[34] Some began to move away. This was exacerbated by the arrival of the emancipated peoples of John Randolph from Virginia.

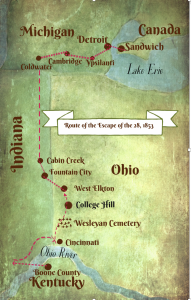

Randolph was a Charlotte County, Virginia tobacco plantation owner who upon his death bed, changed his life long belief in slavery, and emancipated 383 people in his will. More than that, he set aside money to purchase them land in a free state. The people were to be resettled together. After years of study, debate and challenges as to the sanity of Randolph when he wrote his will, Judge William Leigh purchased 3,200 acres in German, Granville, Butler, Franklin and Marion Townships, Mercer County, in 1846. The prosperity of this area and Wattles’ assurances that the whites were comfortable with Carthagena, resulted in the start of the emigration to Ohio. Sixteen wagons traveled with those walking though Virginia until they reached the Kanawha River. Traveling by steamer they arrived at Cincinnati to board four boats on the Miami & Erie Canal.

Word of their travel preceded them. Newspaper articles represented their numbers as 400, and at least one said 4,000. This triggered the white fear of displacement, loss of jobs, and dislike of racial equality combined with fears of becoming a minority population where these manumitted would settle. When the freed people reached Dayton, they were not allowed to disembark. When they reached Piqua to acquire water, they were met by a white mob who turned them away. A few brave people provided them with fresh water and the canal boats proceeded on to New Bremen. There, one day past July 4, 1846, they were met with a hostile armed mob that prohibited the freedmen for going to their lands unless a $500 bond apiece was posted in accordance with the Ohio Black Laws.[35] Mr. Caldwell, the wagon master hired by Judge Leigh to stay with the group and aid in their transport and resettlement, offered himself as hostage to the mob, and was willing to post $1,000 bond to be jailed until Judge Leigh himself could come. (Leigh was in Dayton, on his way to Mercer County when this occurred.) The mob initially refused, but relented and let the group come ashore for that night, to leave by 10 the following morning.

The citizens of Mercer County had drafted a manifesto of their position and wanted to remove “…the entire colored population from the county and to prevent others from settling among us…” and set forth a series of unanimously agreed upon resolutions concerning the removal and non-employment/trade with any black or mulatto person. One resolution accurately defined their position: “That we will not live among Negroes, as we have settled here first,[36] we have fully determined that we will resist the settlement of black and mulattos in this county to the full extent of our means, the bayonet not excepted.”[37]

Escorted by armed citizens, the Randolph exodus was put back on the canal boats. The armed contingent flanked the canal banks until the county line. The people were turned away until they reach Piqua (Miami County). There, they were accepted at the Johnston farm. The local Quaker community assisted them, finding them shelter and jobs. Eventually, after attempts to locate in other areas, the group settled around Piqua, Sidney and Xenia.

Wattles denied to Ohio Governor Mordecai Bartley that the mob represented the majority views of the Mercer County citizens and urged that the question of black settlement should be put to the voters of that county alone. Bartley threatened Mercer County with martial law unless it could keep the peace.

While the black community persevered with only a few families departing, changes were coming. Hatfield sold his land on July 24, 1849 to Reddick Williams[38] for $350. By the 1850 census Wattles had moved to a farm in Clermont County. He was ill, possibly with malaria, and could no longer supervise the daily running of the Institute. In early 1855 Wattles moved with his family to Kansas Territory, settling finally in Linn County. He and his brother founded the town of Moneka and it became an educational center. Moneka was a progressive town of abolitionists and free thinkers. An associate of John Brown, Augustus broke with Brown’s methods which sometimes included killings however Wattles was part of a group that went to Harpers’ Ferry to free Brown from jail. Brown refused their aid and was hanged. Wattles died Dec. 19, 1876 at age 69.

The Emlen

trustees closed the Institute and moved the manual labor school to Bucks

County, Pennsylvania in 1857. The Emlen Institute’s property was sold to the

Congregation of the Most Precious Blood who established St. Charles Seminary on

the property.

[1] Dated Aug. 25, 1826. Her owner had been Elizabeth Moore who moved from Harrison County, Kentucky to Clermont County, Ohio.

[2] Anna-Lisa Cox, The Bone and Sinew of the Land, (PublicAffairs, New York, 2018).

[3] Circa 1852

[4] PublicAffairs, New York, 2018.

[5] Ibid, p 8.

[6] Ibid, p 9.

[7] Ibid, p 10.

[8] Ibid, p 18

[9] Ross Frederick Bagby, “The Randolph Slave Saga: Communities in Collision,” (PhD diss, Ohio State University, 1998), 146-147.

[10] A township is a square, 6 miles X 6 miles= 36 sq. miles (3840 acres). A section is 1 sq. mile of a township = 640 acres. This measurement was set up by Congress in the Land Ordinance of 1785, and was to be priced at $1/acre.

[11]Statutes at Large of the United States of America, 1789-1873, Ch. CVIII, Statute I, May 24, 1828, Twentieth Congress, Session I, Ch. 107, 108, 1828.

[12] Congress in the 1820’s gave about one million acres of the “Congress lands” in Ohio for the establishment of canals across the state.

[13] Bk G, p 304 Deed, Range 3, Town 7, Section 7, Marion Township, Mercer County, OH. Nov. 14, 1835.

[14] Author italics

[15] sites.rootsweb.com/~itcherok/treaties/1828-washington.htm

[16] Included in this group of two dozen students were Horace Bushnell, (minister, teacher and Cincinnati abolitionist), and Henry B. Stanton who married Elizabeth Cady.

[17]Now Northside, then outside of the city limits of Cincinnati.

[18] Donald E. Williams, Jr., “Prudence Crandall’s Legacy,” (Wesleyan University Press, Middletown, Connecticut, 2014), p. 170.

[19] Bagby.

[20] Anna-Lisa Cox.

[21] “From the Colored American. Important Subject,” New York Evangelist, (New York, NY), Feb. 10, 1838

[22] Henry Howe, Historical Collections of Ohio, Vol. II, ( Henry Howe & Son, Columbus, Ohio, 1891), p 504.

[23] The manual labor school movement combined education with working to offset the costs of tuition. This allowed for a broader section of the population to attain education because the fees were not due upfront upon admission. Many had farms attached, where the school raised its own food.

[24] “Anti-Slavery Intelligence,” The Philanthropist, (Cincinnati, Ohio), July 7, 1837.

[25] “From the Emancipator, From Mr. Wattles,” The Philanthropist, (Cincinnati, Ohio), Oct. 13, 1837.

[26] Ibid

[27] “Baptist Church Disappears After Nearly 100 Yrs.,” Daily Standard, Dec. 24, 1934. Thanks to Mary Ann Olding for this article. “Free Will Baptist” followed the beliefs espoused by Benjamin Randall.

[28] Howe

[29] “Negro Colony in Ohio,” The Evening Post (New York, NY), July 24, 1843

[30] “Colored Settlement,” Emancipator and Republican,( Boston, MA), Dec. 3, 1845

[31] Championed rights for the “common man,” if that man were white. Approved of the patronage system, was against the “elite” class and higher education, approved of slavery, against government al influence on the economy and the supported “manifest destiny.” Named for the tenets of President Andrew Jackson.

[32] Jill E. Rowe, Invisible in Plain Sight, (Peter Lang, New York, 2017) , p 76.

[33] Bagby

[34] Rowe

[35] Repealed in 1850 when Ohio’s Constitution as ratified.

[36] Although not true

[37] Rowe

[38] Race unknown, not in the 1850 Ohio census

Previous Post

Previous Post Next Post

Next Post